Practice Perfect 851

Decision-Making: The Most Important Skill Not Utilized

Decision-Making: The Most Important Skill Not Utilized

While watching a YouTube video about the 10 “most important” life skills, number 9 was about decision making. This resonated with me, so let’s decide to talk about decision-making. I’ve actually written about this before; in fact, many of the articles I’ve written over the years are either directly or in-directly about this topic.

For physicians and surgeons, this is one of the key skills that we must master, and yet we spend so little time discussing this and learning about it during our training. Think about your own experience going through your training. In school, you received lectures about various pathologies, and when it came to the treatment aspect, you received a list of options. Prescribe one of these medications for this problem. Choose one of those surgical procedures based on some radiographic or clinical parameter. Then, depending on your residency, you may be told what treatment method to employ. This “works in my hands” you might have heard. This vague and generally useless statement tells us nothing about why something works. These methods are proscriptive and don’t rely on any actual thought process or decision-making. Then, when a new doctor enters practice, they must make decisions in situations that are often ambiguous or don’t have only one correct answer. The real-world forces us to become decision-makers.

The real-world forces us to become decision-makers

Decision Paralysis

For some people, making a decision can be very difficult. Often this is due to having too many choices. If there were only one option, then making a decision would be easy. There simply wouldn’t be a decision. Making a decision, then, requires more than one option, and this can be scary. We can’t read the future and we can’t predict the results of our decisions, especially unique decisions with potentially life-altering outcomes like the choice of a spouse or job. Decreasing decision paralysis requires two tools: having a framework and building experience.

Have a Framework

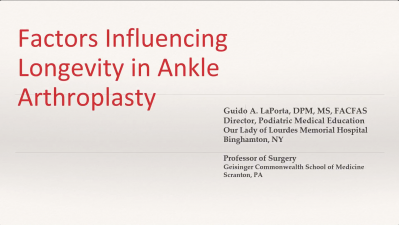

Perhaps the most useful idea is to consider the importance of having a framework in which to refer when making decisions. As a physician, one must have an organized framework for diagnosis and treatment. This is the reason I’ve written ad nauseum about a process for podiatrists I’ve termed the kineticokinematic (KK) approach. In summary, the KK Approach is as follows:

- Step 1: Determine the damaged anatomy.

- Step 2: Determine the contributing biomechanics.

- Step 3: Treat the underlying biomechanics.

I know you’re thinking this seems obvious and overly simplistic, but I respectfully disagree. Think of a common pathology you treat and ask yourself how you decide your treatment plan for that pathology. Other than listing a recipe to treat X with Y intervention or “this is what I learned in residency,” can you describe a clear decision method? Take, for example, hallux valgus. I use the above 3 steps to justify both my nonsurgical treatments and surgical procedure choices. I could sit down with you and describe, using these 3 steps, why I prefer certain shoes and orthosis modifications and why the Lapidus bunionectomy is my first choice for surgical procedures. Having a framework is so important that I spent 12 editorials (Practice Perfect 823 – 834) to break down clinical decision-making.

Generalizing this idea out a bit, think about life decisions. Why did you decide to go to medical school? Why did you choose a certain type of practice instead of another? Why are you employed by a private practice versus a hospital? Why are you not a lawyer or an accountant? Likely, the choices you made fit into some picture of how you want to live your life or are reflections of what is important to you. Perhaps you’ve chosen your path because of some greater purpose. I’ll bet that those of us who make life choices this way are generally happier than others who simply chose what was easier or more expedient at the time.

When making any decision, especially if it’s one in which you’re not certain, weigh that decision against your own framework. Don’t think you have one? You likely do to some extent, but perhaps it’s not as clear to you as you might like. Where am I going to work after residency? Should I take this job or that one? Think about what’s most important to you. What is your purpose? Will X position satisfy that purpose?

Practice & Analysis Makes Better

Like any skill, decision-making requires practice. Experience is a harsh teacher, but it’s the best one we have. The more experience we have, the greater is that well of knowledge from which to draw when making future decisions. Choosing treatment X for a disorder will yield a result, either positive or negative. The patient will improve, worsen, or remain unchanged. Making the decision to take this job will yield a specific set of outcomes, while choosing that one will end with a different outcome. Clearly, there’s a certain element of trial and error in anything.

Experience is a harsh teacher, but it’s the best one we have

We learn from the results of those decisions, but only if we analyze those results and look for the lesson. We have to honestly, clearly, and – perhaps even brutally – analyze the outcomes of our decisions to learn and grow. On a professional educational level, the residency program I run is structured to push our residents to analyze their outcomes. What decisions were made during that surgery? What could have been done better? What did you learn? Why was that medication prescribed to that hospitalized patient? What was the outcome? Could something different have been done? What principles were used to make that decision? Honestly and openly considering alternatives and outcomes is the only way to improve. By doing this, we are building a personal library of experience from which to draw.

Experience must be built in the right way, through conscious analysis. One of my current residency attendings is a highly experienced trauma surgeon. He’s very good at what he does and has excellent outcomes. When he lends his perspective, I listen carefully. But as common as his excellent advice is, equally common are “I don’t know the answer” comments. He openly and unabashedly admits when he doesn’t know the answers, and he seeks out those answers whenever possible. The reason he’s so good at what he does is because his years of experience have been spent analyzing what worked and what didn’t. It’s legitimate experience.

For those of you familiar with the work of Anders Ericsson, the cognitive psychologist who studied expertise, this approach to decision making is deliberate practice for our lives. Dr Ericsson’s book Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise is not about making decisions, but you’ll see the mindset and its powerful applications to making decisions in both professional and personal life.

Best wishes on future decisions.

Jarrod Shapiro, DPM

PRESENT Practice Perfect Editor

[email protected]

Comments

There are 0 comments for this article